Sister

Sister

14

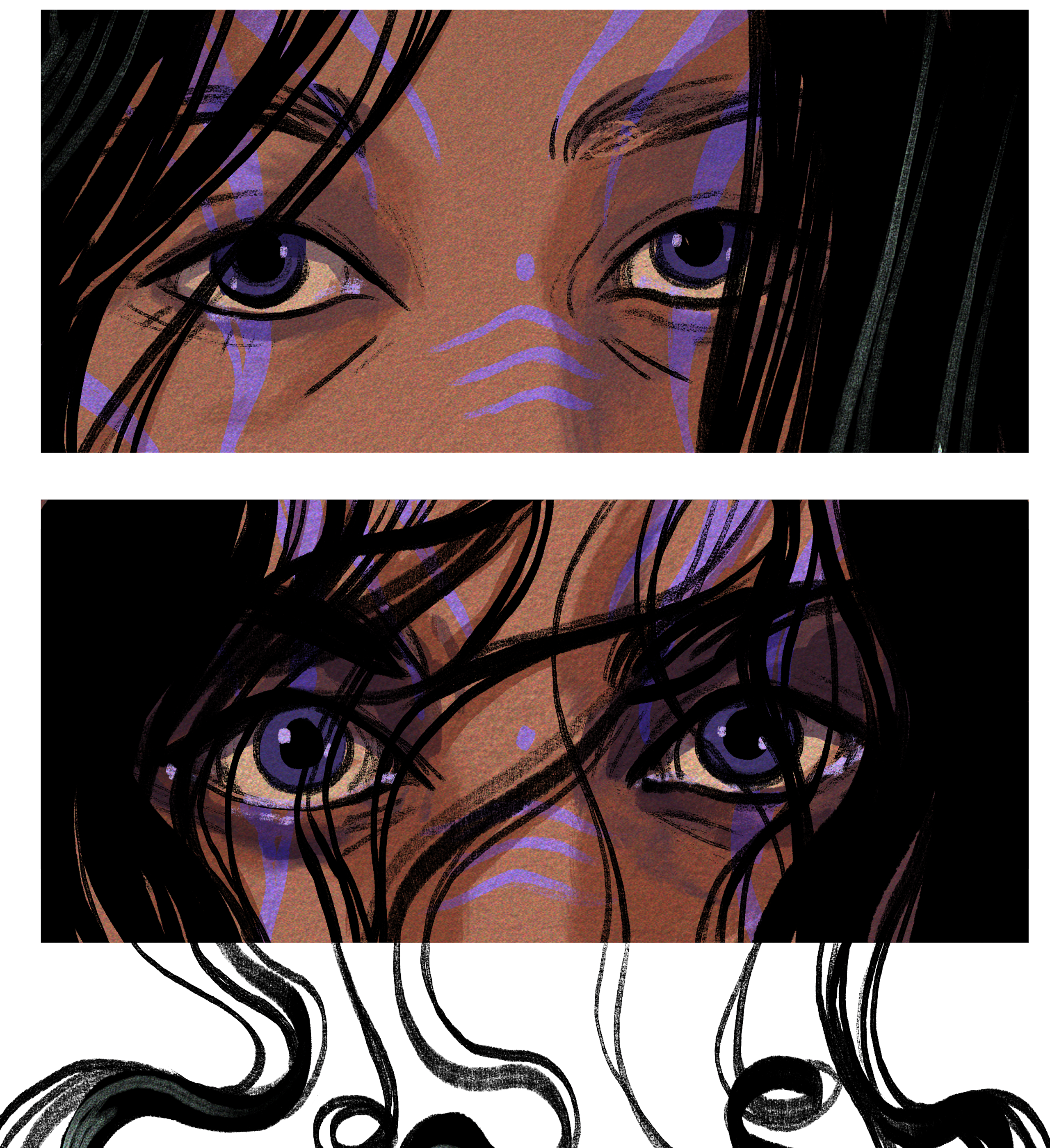

Fig staggered and fell back onto the woven floor. The doll of her sister shook with fury. Iraya. Fig traced the wicked curve of her brows, the scowl of her mouth. There it was — something truly familiar.

Iraya swayed. She tried to support her torso with her arms, but they wobbled and bent. Blood from her cut palm seeped into the bedding as if it, too, were pierced. She fell back onto her pillow.

Fig ignored her own injured palm and crawled forward.

“Touch me and I’ll kill you,” her sister rasped.

Fig glanced at the door to the room. The commotion had yet to summon an attendant. “I’m not here to hurt you,” she said slowly.

“I know who you are.” Iraya spat at the ceiling.

Fig tense as her heartbeat climbed between her ears.

Iraya attempted to speak but only croaked. Fig leaned forward to hear.

“I said,” Iraya coughed, spine curling, “leave.”

“What happened to you?” Fig whispered. She heard crickets preening beyond the paper walls, the mild bubbling of the hot springs. She clung to these noises above the echoes of haunted whispers, the screams of the dying, the laughter of Iraya’s pack as they hoisted her upon their shoulders.

Despite Fig’s efforts, she could not tear herself from the two memories of her mother — one her own, the other a warped reflection. The same stories, the same methodical voice. It had been so long since then. She was so tired.

“Are you crying?” Iraya seethed.

Fig returned to the room. This dim, bamboo box gone stale with years of silence. Iraya’s voice was almost their mother’s. Slightly higher in pitch. Angrier.

Fig traced the lines of her sister’s tattoos with her eyes. “Where is our mother?”

Iraya snarled at the word. She hoisted herself up again and winced. Hair fell over her shoulders in crazed webs and her eyes narrowed to slits. “The bile that birthed you is not my mother. You are not my sister. You are nothing to me. Less than nothing. A stranger ripped from a grave.”

Fig felt her own anger rise. She had abandoned everything she’d ever known, journeyed until her legs shook, lived on scraps in the wind and snow. She had risked her life for people who could not look her in the eye, had accepted death beneath the knife of a witch. She knew what it was to be nothing. She knew what it was to be alone. There was only one person who could save her from that.

Her delusions of sisterhood shattered. “You want me to leave? Tell me where she is,” she demanded.

Iraya’s chest heaved, her expression wide like an animal. “If I knew where she was, she’d be dead.”

Fig believed her. The hate emanating from her was unmistakable. Fig had lived it, inside her head. The hatred that sharpened her fingers to points, that ripped through flesh and screamed for more.

Her first instinct was correct. Iraya did not deserve to be awake.

She stood. Her sister grew small, curled upon the floor.

“Then rot.”

Iraya cackled as Fig turned to leave. The noise unraveled into a fit of coughing, then a thud as her body again collapsed into the bed. Fig turned at the door to see her still again, a doll again, her breath slowed to almost nothing.

Gone.

Fig found Akane carrying a stack of dirtied dinner trays up the path to the kitchens. She caught up to the older woman and offered to halve her burden. As they walked, the stone path flickered in lantern-light.

Fig’s steps were heavy with anger. Akane snuck glances at her from the corners of her eyes.

“She woke up,” Fig snapped before she could ask. “I talked to her.”

“Really?” Akane stopped, trays clattering as her arms dropped in shock. “That’s good news.”

“She hates me. If she could move, I might’ve been killed.”

Akane paused, then continued to walk. “That is less good news.”

“She is as vile as her mind,” Fig ranted. “Petulant and dangerous.” She remembered Cathea’s vocal displeasure at occultists and laughed darkly. Perhaps the hag was right.

“Is she still awake?” Akane asked.

“No, she’s back the way she was before. She wasn’t up for long.”

Akane only nodded as they entered a wide, squat building Fig had only ever seen from the outside. Its interior smelled of cedar and chrysanthemum. At its center lay a large, circular fireplace covered with a metal grate and surrounded by tools. Akane set the trays in a nearby wash basin and handed Fig a tea kettle to fill with water. She sat and wiped cups as Fig complied.

“If you are truly scared, you can leave her,” Akane said as she placed the kettle over the fire. “No one here will force your hand.”

“I thought you believed it was her right to wake?”

“Just as it is your right to leave,” Akane declared. “I will continue to care for her. Perhaps another will come, perhaps not. Either path, it is I who swore an oath to Dove, not you.”

If Fig left now, she would still have nothing to go on. If her mother was alive, only capture could have kept her from returning to the house. And capture meant Vaani had taken her, Vaani who could go anywhere. If the enchantress had returned home, to a city in the Wastes, then Fig had no knowledge of its terrain, no map to guide her steps. She had shuddered often over the thought of wandering aimlessly in wind and sand, turning to dust beneath the beating sun.

No. Iraya had the information she needed, she was sure of it. And, darker, in the depths of her mind she attempted to subdue, Fig hungered for the magic she’d touched through the gauze of memory. She had felt it writhe beneath Iraya’s skin like a millipede, each tap of its thousand legs electric. She had felt the fire of it, real, molten, against her palm the moment Iraya awoke. She ran her thumb over the unblemished skin that minutes before she would have sworn was seared and raw. Magic. The emptiness inside her roared at being so desperately, momentarily satiated.

Akane watched her indecision flicker. “If you commit to waking her, you must be prepared for the person she is, awake. Not just a collection of memories. A witch. A deeply scarred witch. A danger to you, and to others. To herself.”

“She’s hurt people,” Fig whispered. She felt the squelch of the man’s neck beneath Iraya’s blade. What use was information, magic, if she met the same fate?

“I believe you.” Akane nodded.

“She wants to hurt me.”

“I believe that, too.”

Fig frowned at the older woman. “You don’t seem scared.”

“If my sisters killed me each time they threatened to, I’d be dead a thousand times.” Akane poured tea into two cups.

“This is different,” Fig protested. “I don’t know her.”

“It is,” Akane agreed, sipping. “You don’t trust each other. Trust is something to earn, or to bargain for.”

“Bargain for?”

“Why are you here?” Akane watched her from over the rim of the fine clay cup. “You are kin, but you don’t know her. Why come for her?”

“I never knew our mother’s pack — Iraya’s pack,” Fig began, struggling for some truth. “If I understand her mind, they are dead.” The force of Iraya’s grief was unmistakable. She recognized it reflected in her own, multiplied tenfold. “Iraya and I may be the last. I need her.”

Akane’s face stilled. Steam from the tea billowed before her. “Then you must make her understand she needs you too.”

The visitors’ quarters were a long, rectangular building past the kitchens. The woven floor was lined with nooks for down sleeping mats. Fig worried Iraya might wake in the night and kill her while she slept, and Akane did not do much to assuage her fears by agreeing. Fig counted space for at least two dozen visitors, but only two beds, at opposite corners, were made up. Akane unfolded a screen to block one side of her space, though it did little to block the draft in the tall, airy room.

“Who else is staying here?” Fig asked.

“I won’t speak for them,” Akane replied. “Many, both ward and visitor, prefer anonymity.”

The folding screen she had chosen was one of many throughout the room, each with a different painted pattern. Fig’s bore an inky impression of the mountain with a blindfolded woman winding her way to the top.

“This is beautiful,” Fig marveled. Each brush stroke was singular, restrained. The paper was so thin firelight glowed from behind like the setting sun.

“They tell the story of our founding,” Akane explained. “Those in need walk in Dove’s steps.”

“Was she a witch?”

“Yes, though no one can agree on what kind. I’ll tell you the tale, if I see you again.”

If. The possibility of her departure hung between them. Fig searched the older woman’s face for answers, but found only that useless, small smile.

She sighed. “Goodnight, Akane.”

The next morning, before dawn, Fig returned to Iraya’s quarters. She slid the door open slowly, as if she might find her sister behind it, armed, ready to strike. But she was exactly as Fig had left her. Still as a corpse, face unmarred by fury. Fig took a deep breath as she crossed the threshold. She was in control.

Someone had come and replenished the candles. Though the room flickered with firelight, the blue dawn rendered Iraya’s skin almost gray, the lines of her tattoos like water dripping from leaves. The cut from the night before had been cleaned and dressed, her bedding replaced. Akane must have understood Fig’s discovery, for she had left out a tray of successively larger bandages and twice as much cleansing water as before.

Fig found another scar along Iraya’s forearm to part with her knife. As she pressed her hand to the wound, she focused her mind on the memory of their mother in the field — the timbre of her voice, the way her fingers drew lines between the stars.

Ice had frozen a spider’s web. Dew hardened to shards. Somewhere behind her, someone was chanting. It was an old song. Older than her, than this clearing, than this spider without the means to shiver in the cold. Mother sat beside her, bored. Mother hated the chanting. She wondered if the spider could walk across its own silk, shiny and hard, without sticking. She wondered if it would feel the fear of its bundled prey — alive but unmoving, enshrined. She wondered if it had no choice but to cause suffering, to reap suffering in return. She summoned a small flame flat against her palm. Mother smiled. Mother reveled in curiosity. She warmed the web and listened to water fizzle into steam.

Steam had stained her kin’s hands pink. Brine and Epo had discovered a new kind of flower, one which released juice as bright as its petals. They had boiled basins of water with the juice, were experimenting with dipping various fabrics inside. The water was warm against her skin. She couldn’t help dipping her arms to be dyed, splashing water at her elders like a bear cub by the river. They sent her the memory of the last dye day, of everyone’s skin freckled with shades of green and brown. Mother was not in the memories. They reflected her disappointment, flooded it with more angles on the day. She lined up the memories with her sight, blinked between pink and green, green and pink.

The throne room had been the pinkest thing Brine had ever seen. Ruby fabric hung from the ceilings like the many tongues of some Beast. She saw the room through Brine’s eyes — she was short, closer to the ground, seated upon it. Even the ground was glorious. Intricate tiles in blues and purples that slotted into diamonds, flowers. The pillow beneath her was soft like a bird’s chest feathers. The leader had set a large table for all of them — her own advisors and the pack. It stretched the entire room, cavernous and glittering. The leader glittered most of all. The silk of her cape was woven with gold. It parted over her swelling belly like the river around a stone. Her eyes were hypnotic. Brine struggled to focus. The rest of the city witches were like that, too. Soft skin, fragrance rubbed on each wrist, behind the ear. When they moved, the yards and yards of silk rustled like rainfall. Brine felt the experience ripple through everyone. She was chastised. They needed to focus. The leader was speaking. She was meant to listen.

Listen, Clover whispered. Can you hear them? Wings cut through the air like a chorus of strings. She opened her eyes to see a flock of birds so pale they were near wrought from glass. Clover smiled, her lips parted like a cut peach. For a moment, she was struck to silence by the soft planes of the seer’s face. The slope of her nose, the curve of her jaw. Irids. Just like I remember them, Clover sighed. They sat on the edge of some cliff, the trees beneath them lavender with sunset. She wanted to speak, but her mouth filled with sand. Clover’s skin lightened to a pale green, hardened. Water rose over the treetops. Clover stood before her body turned entirely to jade, raised her arms, and dove in.

“No!” Iraya yelled, wrenching herself upright. Her chest heaved. “That’s not what happened.”

Fig returned to herself, to the bamboo room. She panted through the panic that was not her own, rifled through each stolen sensation until her head thrummed. She pushed the other visions aside and grasped at the foggiest memory, the memory Iraya herself had claimed from another. The ruby room, the row of witches in silk. She recognized the fabric — the drape of it, the shine. She saw the echoes of Vaani in their faces — the leader most of all. Thick, arched brows, tall mouth, warm skin. They were the enchantress’s people. Fig was sure of it.

“Who are the witches in silk?” she demanded.

Iraya looked around the room, dizzy. It took her a moment to focus. When she saw Fig, a mask of anger snapped over her fear.

“They are important,” Fig continued. “Tell me what you know of them, and be rid of me.”

Iraya patted her sides as if searching for a knife.

Fig held her hands up in a panic. “What I’m doing, it’s the only thing that can wake you. Your caretakers say you barely move, barely breathe. Your heartbeat comes so slow it’s as if you’re dead.”

Unarmed, Iraya’s body tensed to spring forward, fingers clenched into claws.

“You need me,” Fig sputtered. “You’ll never see Clover without me.”

It was a guess. The Clover in Iraya’s mind was an echo of an echo, a foggy reflection of the witch from Fig’s own dreams. But something had connected. Iraya’s longing was unmistakable. It mirrored the way Clover spoke of Iraya, of the desperation in her voice at the prospect of coming here herself.

Iraya’s breath hitched.

Fig waited.

Finally, sharply, “Is that a threat?”

“It’s a fact.” Fig shrugged, faking the nonchalance Wren displayed when deflating Altair. “You’ve been here for years. You’ve never woken, all that time. Clover guides me here, and now you’ve woken twice in as many days.”

There was a long pause. Iraya glared at her. “Clover sent you?”

“Yes.” Her deal with Cervus need not be at the front of her mind, not yet.

“Prove it.”

“Her magic tastes like stringed sugar.” Iraya’s narrowed gaze traced every surface of her face. She began to sweat. “You know, when the baker gets it so hot it turns brown, then spins it over a wooden spoon—”

“I know what stringed sugar is,” Iraya spat. She turned away. “I believe you.” Fig listened as the candles devoured their wax. Then, a whisper, “It’s been years?”

Fig held her breath. “Your attendant’s name is Akane. She says it’s been ten.”

“How many years do you have?”

“Twenty, when the leaves fall.”

Iraya pulled her arms around her shoulders. Fig stared at the curve of her back.

“Do you know where you are?” she ventured. “This is the Asylum. It’s a resting place for witches who have lost a piece of themselves.”

“Twenty,” Iraya whispered to the wall. “Twenty years.”

Fig was losing her.

“Who are the people in draped silk?” she repeated. “Dark hair. Big, elaborate room. One of them was pregnant.”

“Enchantresses,” Iraya muttered. “Cursed enchantresses.”

She knew them.

“What would one of them want with our mother? Would they kill her?”

Iraya laughed but it was a dark sound. “No, they wouldn’t dare. They’d think they need her alive.”

Her mother lived. The hope within Fig spun and sang.

“Where would one take her? If they were to find her?”

“You have no idea, do you?” Her sister’s voice was laced with an exhaustion she did not understand. “She didn’t breathe a word of it?”

It was Fig’s turn to be silent.

“Her perfect child,” Iraya seethed. “Untainted.”

Fig felt the mood turning. She needed more. “The enchantresses called her kinslayer. Does that mean anything to you?”

Iraya laughed again, “It rings of the truth.”

“What does that mean?”

“I can’t recall.”

“Where do these enchantresses live?”

“I can’t recall.”

“You’re lying,” Fig accused.

“Perhaps.”

“Help me,” she demanded.

“No.”

“Please,” she insisted, begged.

“No,” Iraya repeated louder. “I don’t owe you anything. If my luck turns, they’ll come take you, too.”

Fig felt her entire body vibrate with frustration. She dove for Iraya’s wounded arm faster than her sister could pull away. As the blood slipped between her fingers she thrust her mind into the space between their flesh.

She was back in the golden room. It was clearer, now. The leader of the enchantresses had bright orange eyes. The pack shifted in their seats. Light reflected off nearly every surface. They did not like to be so exposed. I’m pleased you’ve agreed to meet with us, the leader crooned, her voice smooth and deep. I respect you deeply. I’m grateful for your help, and confident that we have much to offer you. Brine felt the hum of agreement through all of them. They had discussed their demands before coming, what they were willing to part with. She took the hand of the kin to her left. Something was wrong. It was wet. When she turned, she saw blood pouring from her kin’s chest, spouting onto her lap and the joining of their hands. She screamed.

She was in the forest. The snail-shelled hag had armored her torso with magic, but no matter. The head of her halberd pressed through magic and chest both with a horrible squelch. She saw her foot press against the hag’s back as she reached for the shaft of her weapon and pulled it through.

She hefted the weapon and threw it. She was in snow, but she couldn’t feel the chill of it against her legs. It punctured the shoulder of a slender man running ahead, erratic like a fawn. He fell to the ground and writhed, ice turning pink. She yanked the blade from his flesh before swinging it down on his throat.

“Stop!” Fig shouted, tears hot against her cheeks. The wet crunch of violence echoed. The candlelight of the Asylum flickered behind her eyes. She pulled back but felt Iraya’s hands too strongly against her arms, holding her in place.

“This is what you wanted, isn’t it?”

It was daylight. She stood in a field of grain, still green with spring. A mother lay over her child, blocking his body with her own. Please, she begged. I need more time. She summoned a flame between her palms and lit them both ablaze.

Fig used all her strength to flip Iraya to the floor beside the dais. Iraya hooked her leg around her hip and continued to roll them, pressing Fig’s arms to her sides.

“This isn’t what you sought to steal?”

The visions came faster. Halberd slicing through stomachs, through legs, hacking out hearts. Fire crisping flesh, licking up walls, burning wounds closed just to cut them open again. Blood pounding, blood hardening, blood fashioned into claws for ripping, tearing, ending.

Fig screamed and kicked Iraya so hard she heard the air wheeze from her chest. Her sister fell back onto her haunches but sprung forward again to grab at her ankle, blood smearing between them. Fig tensed her entire body, willed the magic of it to melt into her skin.

She was looking at Iraya from the outside. She was young. She held up a rabbit, grinning. She was lying in the river. She was skinning a deer. She was walking with her kin through the meadow. She was on top of a tree singing to the stars. She was looking for Iroche, lonely Iroche, begging her to come home. She was screaming. She was too late.

Iraya scratched at her leg until her nails pierced Fig’s skin. Fig kicked and kicked but they only dug deeper. Visions of killings came so fast she couldn’t tell them apart. Blood on her arms, blood on her chest, blood wiped around her chin by her tongue. Then, she felt a heat beneath her hands. A shock like her hair lifting as she crept towards a tree struck by lightning. A wholeness that calmed her head like the darkness just before sleep. Iraya’s blood lifted from her palm and undulated like a bird’s wings. She felt her sister tugging on her but it was far away, now; half-speed. The blood hummed a song she hadn’t heard in a long time. It begged for flight.

She let it fly.

Iraya ducked as the blood hurled forward. Fig’s head pounded so hard she couldn’t see, but she heard the rip of paper as it pierced the paper screen wall at speed.

“How dare you?” Iraya snarled, scrambling to her feet. She pressed a foot into Fig’s stomach until she felt she might vomit. Fig blinked against dizziness as Iraya stood over her, her fists balled as if she were holding her halberd.

She was going to die. She raised her hands over her face. She felt Iraya’s leg quiver. Then she saw the room from her sister’s eyes for a moment, spinning sickly.

Fig held out her arms to catch her before she hit the ground.

Akane said she had found them that way — tangled together and smeared with blood. Fig wasn’t deeply injured, just scratched in long, stinging lines. She woke in the visitors’ quarters with bandages of her own, her head reeling. When she found Akane to tell her what happened, the older woman did not remark on much at all. She only showed her the hole in the screen wall, smaller than a fist and ringed in dark red, and then the workshop and how to repair it. Fig worked in a haze. She asked if Iraya had woken at all. She had not.

When she returned to the room, she did not dare touch her sister. She wiped her head with a wet towel, sat in the candlelight, and watched Iraya’s stillness. She tried to distance herself from the layers and layers of death. She did not succeed.

What she had acted upon was magic, she was sure of it. Not just listened to, smelled, felt — but channeled. Used. As easy as breathing. It had felt like it did in Iraya’s memories magnified by hundreds. It was terrifying. Addictive.

She spent two mornings like this. She spoke little. She folded into the fabric of the Asylum, its days of uncertainty and quiet. When not at Iraya’s side, she volunteered in the kitchens, the laundry, the workshop. It grounded her to debone fish, rake sheets over a washboard, hammer wood slats into place. While at first the Asylum’s leisure had been a welcome respite from the hardships of travel, FIg had grown restless. To be of use was to be closer to her previous life.

The moon waned by the time she worked up her courage to touch Iraya again. She regressed to the needle, to just a pinprick on the finger. She made a conscious effort to empty her mind — seek nothing, receive nothing. She found a small warmth like a leaf brushed by a spark. She focused on nurturing it, and it alone.

Finding Iraya this way was much slower. On the fourth day of trying, she attempted to calm her breathing and open her mind not to Iraya’s memories, but only her magic. It hit her with such force she fell immediately unconscious. When Akane found her, she did not have words to explain it. It was unlike anything she’d ever listened for, like being crushed under a mudslide of noise. Her ears rang for hours. She did not reach for it again.

As a quarter of the moon receded to darkness, Fig nurtured the kindling at the center of Iraya into a tiny flame. She felt her sister stir, blink awake slowly.

“I’m sorry,” Fig whispered once she knew she could hear. “What I did was out of line. It won’t happen again.”

She turned her head. She heard Iraya sniffle and cry. She left.

The next morning, Akane surprised her with the news that Iraya had woken on her own.

“I’ve prepared breakfast for you both. She says she’d like you to join her to eat.”

Fig wavered. “Did she seem mad?”

“No,” Akane replied, impassive. “She’s quite well, actually.”

Akane had set up a short, wide table in the center of Iraya’s room. It made the space smaller, more intimate. When Fig entered, Iraya was bent over her plate, scarfing rice and fish with both hands. It was strange to see her upright, the whole of her body functional. She balanced an elbow on one knee, the other flush to the ground. Her hair flowed over her back and across the floor like slithering tar.

Iraya heard the door open but did not acknowledge it. Fig walked, tentative, to stand at the second place setting. The steam from the fish made her stomach growl. Iraya did not look up as she served food onto Fig’s dishes and beckoned her to sit.

Fig rested first on her heels, twitched in discomfort, then shifted to her side. She was off-balance, wavering between flight and food. Hesitantly, she crossed her legs. Iraya only continued to eat. Fig reached for a pinch of rice, then a second.

When her sister finally lifted her head, Fig was taken aback by her beauty. She was flush with life, oiled and strong.

“Did she raise you to eat so daintily?” she asked.

“No,” Fig blushed. “I’m nervous.”

Iraya stared. “Did she raise you to be so honest?”

“No.”

Fig ate more heartily. The room echoed with just the crush of their teeth.

“Are there more of you?” Iraya finally asked. Calm, her voice was closer to their mother’s — resonant and firm.

Fig struggled to focus on her words.

“More what?”

Iraya only waved her hand at Fig’s face, her brows furrowed.

Fig guessed what she meant. “No other children. Just me.”

“Hm.” When Iraya moved, the hair trailing behind her wound along the floor. Strands fell over her shoulders, her face, caught grains of rice like frog eggs in a stream. Fig’s mother always braided her hair behind her neck before eating.

“There were others,” Fig ventured, pausing between each word as if her sister might gnaw at her as messily as the fish. “When you were young? A pack?”

Iraya stilled. “You will not speak of them.”

“Alright.” Fig took a few sips of broth. She remembered only a few of Iraya’s packmates by name or face, their voices blending together in a chorus. There had been at least a dozen, perhaps more. “Your magic — you’re strong. You can make fire. Manipulate your blood.” These were not questions. Fig remembered the pulse of magic from Iraya’s memories, the heat.

“You will not speak of that, either.”

Fig attempted to keep the ire from her voice. “Then what shall we speak of?”

Iraya’s eyes flitted across her face like a lizard. Her irises were lighter than their mother’s, amber in the light. “You’re attuned?”

“Yes.” There was no reason to hide the fact of it. Her sister need not know how, or when.

“Yet I feel no magic in you.”

“I do not wish to speak of that.”

The barest trace of a smile. “You traveled here on your own?”

“I joined a caravan until the mountains.”

“A caravan?” Iraya asked, shocked. “Of unattuned?”

“Yes,” Fig huffed.

“Oh, fitting,” Iraya snorted. “I cannot imagine anything she would hate more.”

“What do you mean?” Fig feigned the sincerity of a girl who had not watched her mother remove a man’s eyes. “She loves people.”

Her sister’s mouth curled in a proper grin. Levity transformed her, for a moment, to a witch less dour, less burdened.

It gave Fig the confidence to venture further. “Why are you apart?”

“Apart from what?”

“From our mother,” Fig clarified, her brow furrowed. “From me.” Despite her confusion parsing the breadth of Iraya’s memories, this was the aspect that eluded her most. There had been a time Iraya and their mother had been together. She had felt the devotion, the intimacy around which she’d laid every stone of her own life. Before Iraya’s collapse, there were ten years of separation. What could have ruptured such a bond?

Whatever had opened in Iraya snapped shut. Her jaw sharpened around her clenched teeth. “Let us understand one another. Iroche is not my mother. She is less than dung, less than mud beneath my feet. You are not my kin. You are a shadow of me, bred to be pliant and dim.”

Fig stopped eating. Fury burned up to her scalp.

“I am only speaking to you because we are of use to one another.” Iraya grimaced. “When that is no longer the case, you will never see me again.”

As if that were a punishment. Fig could stand, leave, and abandon her foul sister to fester. She swallowed the urge to first hit Iraya’s dishes from her hands and spill her breakfast over the floor. “And what use is that?”

“I point you to where they’ve taken Iroche. You take me to Clover.”

The words shredded her anger. Fig felt her voice rise with anticipation. “You know where Mother is?”

Iraya leaned back, her trap laid. Her robe parted to reveal the tattoos trailing down her chest. “Yes and no. They took her back to their city, surely, but it is impossible to find by design. You will need to get to one of them outside their walls — interrogate or trail them.”

Fig struggled to focus over the beating of her heart. “Who are ‘they?’ How do you know they took her?”

“A beautiful witch came for her, didn’t they? Just one, or a pair?” Iraya probed. “They used illusions, dodged her attacks to tire her rather than counterattacking outright?”

Fig only nodded.

“If an enchantress wants you dead, you’re dead long before you catch their scent. If they let her see them, it was a ruse. They were looking to capture her.”

“Wouldn’t she know that as well as you?”

“Her instincts had withered over time, it seems,” Iraya drawled. “More likely, you got in the way.”

Guilt plunged into Fig’s stomach. She had spent countless nights pressing her nails into her palms wishing she had never spoken to Vaani, never trailed her perfume to town. When she was properly overwhelmed by that, she relived each moment of that last night, imagined everything she could have done instead of standing, frozen like prey, then fleeing into the abyss of her solitude.

“Unless the snake has made more enemies in the last two decades, I know who hunted her,” Iraya continued, reveling in Fig’s discomfort. “And I know where to find one.”

“You’ve been asleep,” Fig seethed.

“And you wouldn’t be here if you had other options.”

Fig was vulnerable in that truth. She clasped her hands and took deep breaths as she thought over all her sister had said. “And in exchange you want passage to Clover?”

She clung a facade of impassivity. She had no idea where Clover was. The seer had not visited her again since her arrival. If she did not return with further instructions, how long could she string Iraya along before she noticed?

“Yes, and I already know where she is,” Iraya spat. “You horrible liar.”

“I didn’t say anything,” Fig retorted.

“Don’t need to speak to be foolish.”

“Where is she then?” Fig asked, exasperated.

“The mage zoo,” Iraya rolled her eyes.

“The what?”

“A gathering place for the long-winded to lecture each other to death. She has an arrangement with the witches there.”

Perhaps that was the place Fig had seen behind Clover’s door, the room littered with strange instruments. “How far is it from the enchantress?”

Iraya picked between her teeth with a fish bone.

“You have no idea,” Fig accused.

“I will figure it out.”

“I don’t have time for this.” Fig pinched the bridge of her nose. “If you have ceased being vile long enough to tell the truth — a sizable ‘if’ — and my mother is captive in some city, they could kill her. I can’t be dragging you aimlessly around the wilds.”

“Ha!” Iraya laughed, sour. “You would die in a half-moon without me.”

“You know nothing of me.”

“I see the incompetence in your hideous face.”

“Hideous?” Fig gasped. “At least I have a face of my own.”

Iraya recoiled as if struck. Fig only glowered.

They sat in a long silence.

Finally, Iraya held out her hand. “Give me your knife.”

Fig wore just one of her knives in a sheath below her robe. She shifted her arm to conceal it.

“I already know you have it.”

To propose a deal did not communicate trust, but value. Despite her vitriol, Iraya needed her alive. Fig relented and passed the knife to her hilt first.

Iraya grabbed a fistful of her long, black hair and tugged it taut before slicing the blade through. Severed strands writhed over her knees and lap as she hacked, throwing shorn pieces to the ground in disgust. When she was done, she had cut her hair in irregular, choppy layers, the longest pieces rough against her collarbones. Jagged chunks cut into her forehead, cheekbones, the edges of her face.

She returned the knife wordlessly. Fig used the tip to pluck discarded hair from her food.

“They won’t kill her,” Iraya said, calm, as if their conversation had not been interrupted. “They can’t afford the risk.”

Fig softened her voice to match. “What risk?”

“You’ve heard enough. They will keep her alive until you rush off to save her. I take you to the enchantress, you take me to the seer. A neat exchange.”

Though she tried to hide it, Iraya was losing her luster. She took deep, labored breaths and rested on her arms not from bravado, but exhaustion. Sweat beaded on her brow.

Fig had been confused to see her so lively, but such regression clarified their situation. Her diligence in the past days had brought Iraya to the surface, but whatever depths she harbored drew her back.

“You’re already fading,” Fig sighed. “How would we travel?”

“My condition has to do with magic of the blood.” Iraya attempted to straighten. “You have the blood to help me, in part.”

“In part? Am I your,” Fig searched for the word Helmina had used, “bludsora?”

Iraya scoffed. “No. Bludsora are of entirely the same blood. If Iroche had made us both with only her own. We’re bludkin, as she’s mixed you with another.”

It hadn’t occurred to Fig that Iraya might know more of her conception. “Do you know who he is? My father?”

“That’s a generous word,” Iraya’s nose wrinkled. “And no. My point is, I need you. As a temporary respite.”

“What would that entail?” Fig asked, cautious.

Iraya raised her shaking forearm and tilted it. “Think of my condition like balancing a pot filled to the brim with water. As long as it doesn’t overflow, I can stay awake. Your role is to skim off the top.”

“How?”

“More of the same.” She waved dismissively. “Memories. Blood.”

“I felt something else the other night,” Fig pressed. “Something other than the memories.” The tips of her fingers pulsed with the thought of blood chanting, taking flight.

“You don’t want that.” Iraya hardened. “I will keep it from you.”

“Why?”

“It’s part of my,” she paused, panting, “sickness.”

“That’s not what it felt like.”

“You don’t get to tell me what things feel like,” Iraya replied icily. “We will set rules for what kind of contact to make. If you pull from me like that again, I will kill you.”

The truth of that fell heavy between them. Even trembling, sweating, Iraya’s face sharpened with fury. Fig pinched the space between her forefinger and thumb to keep from shaking herself.

Iraya watched her, gaze narrow like a bird of prey. “What did she call you?”

“Who?”

She grit her teeth against the word. “Iroche.”

“My name is Fig,” Fig replied, raising her chin.

Her sister’s face fell, unreadable. “That can’t be true. She wouldn’t name you something so stupid.”

“It is my name whether you believe it’s stupid or not.” Fig didn’t realize she had become so possessive. Even so, the last thing she wanted to hear was her mother’s name for her perverted by Iraya’s tongue.

Iraya looked Fig up and down as if for the first time, equal parts bewildered and repulsed. “I’m not calling you that. What’s your true name?”

“If you were as wise as you act you would understand why I won’t tell you.”

Their gazes met in further silence. Fig was not curious about what her sister was thinking. Her mind was, as she’d first supposed, vile and violent. She did not look eagerly towards sharing memories again and again during their travels.

Iraya grew pallid in the weak morning light, her eyes blinking faster. As long as she ailed, Fig felt confident in her own safety. Beneath the crust of Iraya’s domineering was dependence. The demon’s voice, which Fig had suppressed for so long, crawled up her spine to her ears, Get her working again, and I return your magic.

She shook off such thoughts. Her mother was her priority. Always.

“You take me to the enchantress. I take you to Clover,” she repeated.

“Yes.”

Fig reached across the table for her sister’s hand.

“Deal.”